Chapter 4 Ethics: Environmental Costs of Machine Learning

4.1 The Problem

Recent machine learning models, such as BERT and XLNet have received state of the art results on common natural language processing tasks. However, not often mentioned is the sheer cost required to train these models. They often cannot be trained on a single computer, and typically require multiple GPU’s in the cloud. For instance, Google’s BERT-large model contains 350 million parameters, and openAI’s GPT-2 contains 1.5 billion parameters leading to massive costs. For instance, XLNet was trained on 512 TPU chips for 2.5 days (Schwartz et al. 2019). As models have gotten more, and more complex, training time can even extend into weeks and months for models that are even more complicated. Recent research has shown that that “training BERT on GPU is roughly equivalent to a trans-American flight” (Strubell, Ganesh, and McCallum 2019). Most severely, the NAS language model, has a carbon output roughly equivalent to the cumulative output of 5 cars over their lifetimes.

Because scientists estimate that carbon emissions must be cut in half by the next decade, this is an “all hands on deck” situation for humanity. The training of Deep Learning models can be quite significant in scope, and also the training of more and more powerful models become more normalized. Thus, rising energy usage in the Deep Learning field, in conjunction with a need to cut carbon output worldwide will lead to increased attention of carbon outputs in the Deep Learning field.

4.2 How to identify the problem

Identifying this problem is straightforward. Most machine learning practitioners are not training Deep Learning language models for months at a time. In addition, training machine learning models on local machines is likely fine. However, those who are training large machine learning models for days at a time will likely encounter questions regarding the carbon impact of their model. Specifically, this issue pops up at scale when one is training a model across heavy hardware, usually on the cloud. Practitioners ought to calculate the carbon costs of their model if this is the case to gauge an estimate of whether or not their model is large enough to trigger carbon offset concerns.

4.3 What can be done

All of these ideas are taken from Lacoste et al. (2019), and the fantastic job they’ve done in outlining what to do to make machine learning more environmentally friendly. Fortunately, there is also quite a lot that can be done to cut down on one’s carbon impact!

Start by measuring the carbon impact of the larger models that you’ve trained and encouraging others to do so. Generally, when a model is trained and productionized for an organization, the creator is responsible for creating documentation covering the models. This is the perfect time to list the carbon impact of your model. Encourage others to measure the carbon impact of their models, the cost is actually quite small and the benefit of such a norm is extremely positive.

If you have a choice, verify that your cloud provider is carbon neutral. Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud are both carbon neutral, and AWS is on the way to becoming carbon neutral (Lacoste et al. 2019). As of 2016, 44% of Microsoft Azure’s energy usage came from renewable sources, and as of 2017, 56% of Google’s cloud energy usage came from renewable sources (Strubell, Ganesh, and McCallum 2019). Another item worth looking at is the Power Usage Effectiveness (the percentage of energy not used on the computing, cooling or other required auxiliary functions themselves).

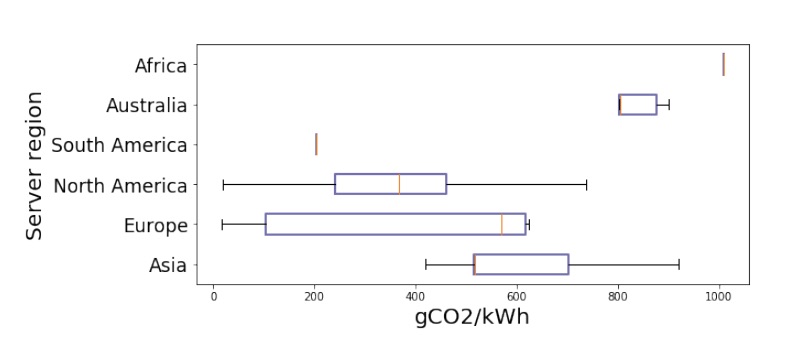

Consider changing your data center location. While a cloud provider may be carbon neutral, a particular cloud center might not be due to the grid that that cloud center is connected to. Typically, data centers in North America or Europe are more likely to be cloud neutral than others. The most efficient centers may be up to 40 times more efficient than the least efficient cloud centers (Lacoste et al. 2019).

Figure 4.1: Carbon emissions from data centers around the world

Be efficient with your code, and hardware! Avoid brute force grid searches for hyperparameter tuning; research shows that random grid search is a more effective replacement. Implement early stopping for any hyperparameter tuning when possible such that the full time required to train a model is not required. Also, be careful with selected hardware. Research shows that GPU usage can be 10 times more efficient than CPU’s, and TPU’s can in turn be 3 to 4 times more efficient than GPU’s. Making sure to choose the right hardware will speed up model training, and in turn reduce the overall amount of carbon locations.

This should go without saying, but don’t train more complicated models than are required! Deep learning is expensive, and if a simpler tool can be used to accomplish the same goal, then it’s likely that that is the way to go!

4.4 Resources

Measure your carbon impact: https://mlco2.github.io/impact/